Once a year, for about a week, all eyes in green building culture turn towards a single focus - it’s been San Francisco, it’s been Toronto, Chicago, Phoenix, and Boston. Every year it is a new city for Greenbuild, the world’s largest conference and exposition dedicated to the green building industry. This year, its 20th year running, it was Philadelphia. I had the pleasure of representing Bialosky + Partners Architects at Greenbuild 2013 this past November. The international convention and expo hosted approximately 30,000 attendees from 90 different countries and touted speakers as varied and prestigious as Rich Ferizzi, President & CEO of the USGBC; Michael Nutter, Mayor of Philadelphia; Nate Silver, author of The Signal and the Noise; and the keynote address was given by former Secretary of State and former First Lady, Hillary Rodham Clinton.

Once a year, for about a week, all eyes in green building culture turn towards a single focus - it’s been San Francisco, it’s been Toronto, Chicago, Phoenix, and Boston. Every year it is a new city for Greenbuild, the world’s largest conference and exposition dedicated to the green building industry. This year, its 20th year running, it was Philadelphia. I had the pleasure of representing Bialosky + Partners Architects at Greenbuild 2013 this past November. The international convention and expo hosted approximately 30,000 attendees from 90 different countries and touted speakers as varied and prestigious as Rich Ferizzi, President & CEO of the USGBC; Michael Nutter, Mayor of Philadelphia; Nate Silver, author of The Signal and the Noise; and the keynote address was given by former Secretary of State and former First Lady, Hillary Rodham Clinton.  Greenbuild is more than just a world-class convention. It is also a networking smorgasbord and showcase of all things sustainable. This year the expo hall was packed with over 800 exhibitors of sustainable products and services. Huge multinational corporations displayed their full suite of green products right next to small startup companies rolling-out their newest gadget or software to a captive, and captivated, audience.

Greenbuild is more than just a world-class convention. It is also a networking smorgasbord and showcase of all things sustainable. This year the expo hall was packed with over 800 exhibitors of sustainable products and services. Huge multinational corporations displayed their full suite of green products right next to small startup companies rolling-out their newest gadget or software to a captive, and captivated, audience.  Multiple parallel tracks of educational sessions provided a plethora of learning opportunities. Lectures ranged from changes in the newest version of ASHRAE 90.1 to low energy lighting strategies, and from net-zero design to insights on the commissioning of existing buildings. Some of the most highly anticipated and well attended sessions dealt with LEED v4, which was officially introduced at Greenbuild 2013. It’s a lot to wrap your head around. Throughout the entire convention, a simple but powerful idea kept presenting itself to me… this is not an isolated, short-lived movement. This is not a passing fashion. This is not a fad.

Multiple parallel tracks of educational sessions provided a plethora of learning opportunities. Lectures ranged from changes in the newest version of ASHRAE 90.1 to low energy lighting strategies, and from net-zero design to insights on the commissioning of existing buildings. Some of the most highly anticipated and well attended sessions dealt with LEED v4, which was officially introduced at Greenbuild 2013. It’s a lot to wrap your head around. Throughout the entire convention, a simple but powerful idea kept presenting itself to me… this is not an isolated, short-lived movement. This is not a passing fashion. This is not a fad.  Whether the adjectives used to describe it are “earth-friendly”, or “sustainable”, or “eco”, or “green”… the fact is, the world is changing. Greenbuild is one time a year when those people keeping track congregate and try to direct that change to be something manageable, and positive, and fun. Another successful year… now on to 2014… this time it’s New Orleans.

Whether the adjectives used to describe it are “earth-friendly”, or “sustainable”, or “eco”, or “green”… the fact is, the world is changing. Greenbuild is one time a year when those people keeping track congregate and try to direct that change to be something manageable, and positive, and fun. Another successful year… now on to 2014… this time it’s New Orleans.

I hope to discuss, in a series of posts, books that have had a significant influence on how I think about and practice architecture. Paraphrasing Thomas Edison, I see architectural design as one part inspiration and ninety-nine parts decision making. The three books I plan to discuss

- Complicity and Conviction: Steps toward an Architecture of Convention by William Hubbard, 1980

- Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution by Paul Hawken, Amory Lovins, and L. Hunter Lovins, 1999

- Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture by Christian Norberg-Schulz, 1979.

address the ninety-nine percent part of the equation. On what basis do we make all of the decisions that ultimately determine what a building looks like, how it is used, and how well it functions? William Hubbard, one of my undergraduate studio professors, described what he called concatenation in design. It occurs when the decision made to solve one problem solves many others and especially when that decision starts a cascade of decisions that simplify what was originally a complex set of problems in design.

Plan for University of Virginia “lawn” designed by Thomas Jefferson

I did not pick up the first book I want to discuss, Complicity and Conviction, until I was in graduate school. In fact I didn’t know it existed until I saw it at the architecture school library used book sale and saw Bill’s name. My understanding of the book is no doubt influenced by what Bill taught me in Studio. The book is in part a response to Robert Venturi’s Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, 1966. Venturi was criticizing modern architecture and advocating for post modernism, Hubbard was criticizing post-modern architecture and advocating architecture that gives “. . . testimony to human values. . .” Conventional architecture “. . . persuades us to want it to be the way it is.” The book explores several potential models for an architecture of convention:

- The Scenographic Style

- Games

- Typography

- and the Law

The Scenographic Style encompasses much of American architecture of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: the work of H.H. Richardson; the Shingle Style of McKim, Mead & White and John Russell Pope; and the Collegiate Gothic Style of Goodhue and others. He helps us to understand a little more about the design and drawing (sketching) technique that was used at the time. While these buildings make good pictures, he finds that they lack meaningful depth, ultimately leaving us unsatisfied. Games are a set of rules that all of the participants agree to abide by. They are a scrim that allows us to be judged not as a whole person but only by the way we play the game. We accept the rules not because they have to be the way they are, but because they provide a concrete framework in which we can enjoy play. We are complicit, agreeing not to question why the rules are what they are. Typography like architecture can provide a Chinese box of levels of understanding. You do not need to be a typographer to look at a page of text and have a feeling about whether you like the way it looks or how readable it is, but practitioners make very conscious decisions about the shape of the page, the size of the margins, the space between the lines of text, etc. Those decisions are usually made consciously, intending to have an effect on how we feel about the look of the page. The reader has the ability to find reasons for wanting it to be the way it is at many different levels. More understanding brings more reasons to want it the way it is. This depth is one of the aspects that an architecture of convention should have. The Law is perhaps the most interesting model that is discussed. His discussion of the law is limited to the way in which judges construct rulings about which we can feel conviction. The best judgments interpret previous decisions in ways that are consistent with what is currently deemed to be right and fair (this changes over time) and allow enough room for further interpretation in future cases. The judge “forged a new link in the chain” of the law, when he does this. Finally the author analyzes two projects that he believes achieve an architecture of convention in different ways. The first example is the University of Virginia “lawn” designed by Thomas Jefferson in the early nineteenth century and the second is Kresge College at the Santa Cruz campus of the University of California designed by Moore Lyndon Trumbull Whittaker in the early 1970s. The author discusses how each of these projects achieves his six attributes of an architecture of convention:

- Slippage – is the link between the form and its possible uses somewhat ambiguous?

- Contingency – does it have features that make sense only because they feel right?

- Are there multiple possible interpretations of the intention?

- Does it call other buildings to mind?

- Are the analogies relevant?

- Does it make us want it to be as it is and not otherwise?

Plan of Kresge College at the Santa Cruz campus of the University of California designed by Moore Lyndon Trumbull Whittaker

When I first read this book it resonated with some of the discussions we had in the Studio (i.e. The modern world has given us many more options for the materials we use and the way in which we put them together, and air conditioning allows us to ignore many of the implications of how the form, orientation, and construction affect the comfort of the occupants.) The modern world has given the architect more “freedom”. We are allowed to ignore many of the “rules” that used to govern the way we designed. The architectural “rule” books by Vitruvius, Alberti, and Palladio no longer apply. This has left us searching for buildings that improve upon the architecture of the past.

University of Virginia “lawn” designed by Thomas Jefferson

Bill leaves us with a charge: “But to realize that this situation has been brought about by our own actions is to realize that it is within our power to rectify it. It is possible, even now, to produce architecture that gives testimony of human values. . . . We must find ways – in all areas of life – to engender in ourselves conviction about human values. We must find ways to convince ourselves anew of human possibility.”

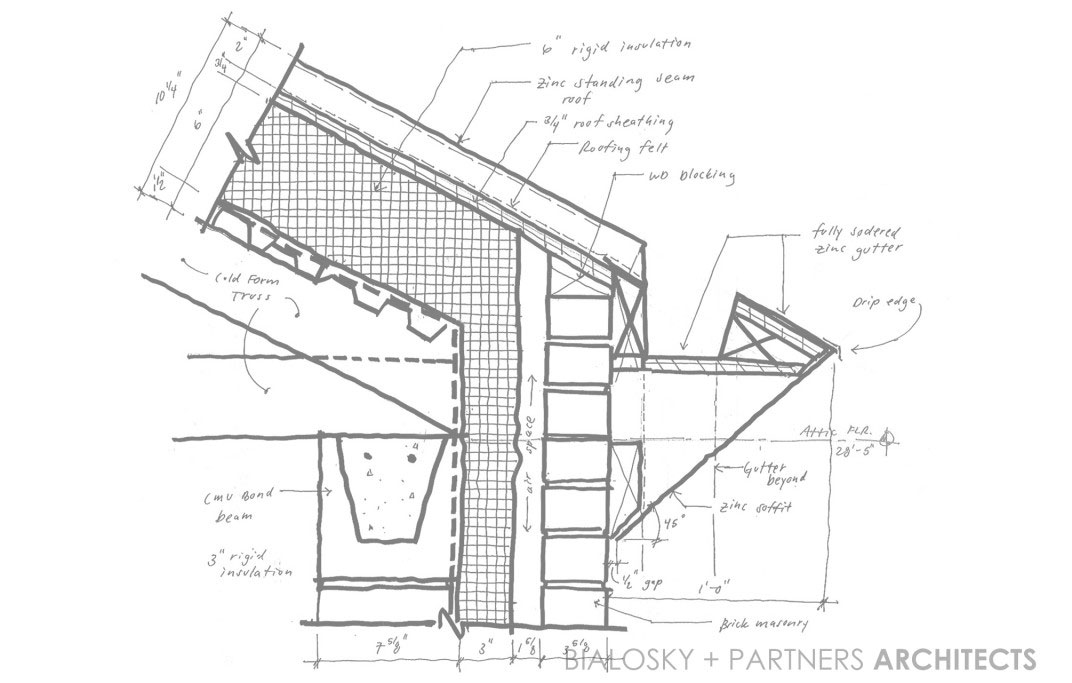

What’s The Big Deal With Continuous Insulation?

Continuous insulation (CI) has been an energy code requirement since the release of ASHRAE 90.1-2004, but unfortunately is still a bit of a mystery to many designers, contractors, and building officials. So, besides complying with the building code, why do we need continuous insulation? Thermal bridging through framing components reduces envelope insulation performance by 15-20% in wood frame construction and by 40%-60% in metal frame construction. This means that a typical 6” metal stud wall construction with R-19 fiberglass batt insulation actually performs at a dismal R-9. When CI is properly installed you get the approximate full R-value of the insulation material. So, what exactly is continuous insulation?

ASHRAE 90.1 defines Continuous Insulation as insulation that is continuous across all structural members without thermal bridges other than fasteners and service openings. It is installed on the interior, exterior, or is integral to any opaque surface of the building. With further research we find that the definition of “fasteners” is meant to include screws, bolts, nails, etc. This means that furring strips, clip angles, lintels and other large connection details are excluded from the term “fasteners”.

This is where the big problem lies, and why the industry seems to be so confused. Many designers, contractors, and building officials are still not informed about this important aspect of CI. For example, masonry veneer wall construction typically employs steel relieving angles and steel lintels at window and door heads. These steel angles are usually fastened directly to the building structure, providing a significant thermal bridge from the interior of the building to the exterior. There are a number of solutions to this issue including welding the angles to standoffs at +/- 4’-0” centers, which allows the CI to be installed behind the angles to minimize the effects of thermal bridging. There are also proprietary clip systems being marketed to perform this same function.

Another cause for confusion is the fact that many building claddings such as metal panels, fiber cement board/siding, etc. are not approved for attachment through more than 1” of non-supporting material. In climate zone 5 we are required to have a minimum CI of 7.5, resulting in a CI thickness of about 1 1/2". There are proprietary systems that have been developed to deal with this issue such as the DOW-Knight CI System . This system has been engineered to allow up to 3” of continuous insulation to pass behind the girt supports. If you or your client don’t desire to specify proprietary systems, the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) commissioned a testing report that describes a number of other fastening system options for continuous insulation. It’s a long read but has a lot of useful information regarding this matter.

In summary, the proper use of continuous insulation is all about paying attention to the details. There are a growing number of resources out there aiming to help designers detail buildings properly. A few of my favorites are www.buildingscience.com and www.bec-national.org . Happy reading, and let’s keep it sustainable.